Who’s in control of the publishing process? Once the contract is signed, does the author have any say in what happens to the story? Traditional contracts specify that the publishing company will publish as they see fit. In other words, control is given to the publisher by the contract.

One criticism of indie authors is that are control freaks. Indeed, many indies will say that control is one of their main issues in choosing how to publish. And that’s seen in a disparaging light, as if the indie author isn’t a team player. From this perspective, the indie author doesn’t understand the publishing process. Editors edit, illustrators provide the art, and each does their professional jobs as part of a team. An author’s professional job stops when the text is finished.

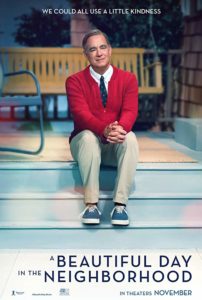

Let’s examine this issue of “control” in the publishing process. To do that, I want to look at an interview on Terri Gross’s Fresh Air NPR program with Marielle Heller, director of “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.”

Hard to believe in your point of view?

Talking about directing a film, Gross asks, “Was it ever hard for you to believe in your point of view?”

Heller responds by talking about moving from an actor to a director.

“But as I started directing, it felt incredibly natural to me more because as an actor, I sort of always felt like I was holding my tongue. Like, when you’re an actor, you’re not supposed to get involved in certain things. You’re not supposed to get involved in every discussion, you know? Like, even if I was acting in a play, and it was a new play, and we were discussing how a scene was working or not working, you know, the director and the playwright might be discussing whether a scene’s working or not. But as an actor, you’re not really supposed to get involved in that conversation. You’re sort of there to do your work.

And I was – I spent a lot of years when I was working as an actor doing theater kind of holding my tongue where I wanted to be involved in those bigger creative discussions, but I knew it wasn’t my place. And when I started directing, it was like, oh, great. Now I get to actually be involved in all of the deeper creative discussions and figure these things out and the problem-solving of storytelling.”

Traditional publishing treats authors similar to Heller experience as an actor. She wasn’t supposed to be involved in the larger discussions, just do the acting and keep quiet. Likewise, publishers make storytelling and marketing decisions without the author’s input. The unspoken comment is that the publishers/editors know best. The unspoken attitude is that the author doesn’t have anything useful to add to the bigger conversation. It’s true that some editors treat authors with more respect and discussed storytelling issues, but not all of them.

Like Heller, I learned a lot by keeping my mouth shut and doing just my part as an author. It’s important to remember that everyone can learn from experienced professionals.

However, there’s also a time for the authors to be brought into the “bigger creative discussions.” And when they aren’t—for whatever reason—one choice is to publishing independently.

For me, and for many other indie authors, self-publishing is a way to become a director of our own stories, to be involved in the “deeper creative discussion and figure these things out and the problem-solving of storytelling.”

Picture Books – Deeper Creative Discussions

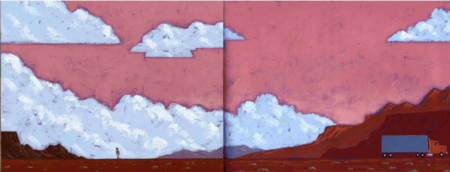

Here’s an example of the deeper creative discussions about storytelling for my picture book, The Journey of Oliver K. Woodman, which was published by Harcourt and illustrated by Joe Cepeda. It’s a story of a wooden man, Oliver, who crossed the United States to connect a family. An Uncle builds Oliver and sends him on his journey. As Oliver crosses the US, he’s given a ride by various people who write postcards and letters back to the Uncle.

There were two crucial decisions. First, Oliver travels from South Carolina to California, a long transcontinental journey. When the book was laid out in the standard 32-page format, it didn’t seem right. Instead, it became a 48-page book with wordless double-page spreads to depict the travel from one location to the next. When the book is read, those extra wordless spreads make it feel like a big journey. A 32-page book wouldn’t have had the same effect.

Second, the editor called me to ask, “Do you mind if we make the family a mixed-race family?”

As Oliver crossed the U.S., he would, of course, encounter a wide range of ethnic groups or sub-cultures. The story already stopped at a Navajo reservation in New Mexico, and Miss Utah was a young Navajo woman. This is counter-pointed by three old white-women who love afternoon tea. A mixed-race family complemented what the story already presented, the amazing multicultural aspect of the United States today.

I was left out of the discussion about 32-pages versus 48-pages. Partly, that’s because it was a matter of budget (48 pages costs more to print than 32), and it was also very much the illustrator’s and art director’s decision. But it was also because, as the author, I was expected to be silent on the issue. But I was brought in on the tail end of the discussion of the family’s make-up.

These two creative storytelling choices—the 48-page length and the emphasis on the US’s multicultural population—helped define the story. It received starred reviews from Kirkus and the BCCB, and was named an honor book for the Irma Black Award, which is given to the story where the story and text are fully integrated.

Indie Published Creativity

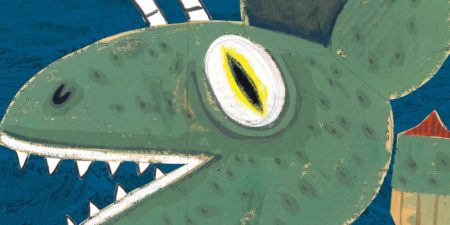

As an indie author-publisher, I enjoy the problem-solving involved in turning a story into a picture book. Like Heller directing a film, I enjoy choosing an illustrator and dividing text into page breaks. The Nantucket Sea Monster: A Fake New Story had a great possibility for a dramatic page turn. This is the story of a publicity stunt about a balloon created for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. People on Nantucket Island are looking for the sea monster.

The text says, “They couldn’t believe their eyes.” This is a good place for a dramatic page turn.

I asked the illustrator to set up the page turn followed by a wordless page that showed the sea monster’s face up-close. At first, he didn’t understand the reason for the wordless spread. But it’s one of the most effective page turns of the book. The text sets up the sea monster’s face close up, which enthralls the reader. However, it’s so close up that the reader is still slightly overwhelmed and doesn’t understand the bigger picture. Zooming in so close reveals and hides at the same time. The next page-turn finally resolves the issue by explaining the sea monster is a rubber balloon, and showing that from a distance. The sequence makes the story more exciting and keeps the reader’s interest.

Exciting page turns and storytelling pacing are just some of the creative storytelling discussions that now dominate my time. As a traditional author, I was mostly excluded from the decisions, but now, I’m responsible for those very decisions.

Heller says, “…I try to involve my actors in that way as well and let them feel like they’re not required to hold their tongue and that we can all be parts of these bigger discussions.”

Like Heller, I try to involve the illustrators and other professionals that work on a project in the creative storytelling discussions and decisions. That’s far from the perception of being a “control freak.” Instead, for this indie author, it’s not a matter of control. It’s a matter of being responsible for the creative storytelling and being able to include others in the deeper discussions.

This is absolutely not true:

Traditional publishing treats authors similar to Heller experience as an actor. She wasn’t supposed to be involved in the larger discussions, just do the acting and keep quiet. Likewise, publishers make storytelling and marketing decisions without the author’s input.

In your example, this:

the director and the playwright might be discussing whether a scene’s working or not.

…is much more how it works, replacing director with editor and playwright with author.