How many times do I start a manuscript and think, “I am lost.”?

Too many.

One of the crucial goals of an opening scene is to orient the reader–quickly, efficiently.

Telling details. The story opens in a certain location and the writer must choose the right details to evoke the story’s setting. By setting, I mean the historical time period, the time of year (season or exact day), physical location and details of that setting, whether indoor or outdoors. And yet, that setting must be in the background of the scene, allowing the characters to come to life in context, but without the setting intruding on the action and slowing down the opening. It’s a tricky balance.

We call such details, the “telling details.” They are small things that evoke the setting, without bashing someone over the head with it.

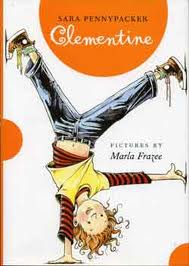

One of my favorite early chapter books is Clementine by Sara Pennypacker. The first paragraph begins like this:

One of my favorite early chapter books is Clementine by Sara Pennypacker. The first paragraph begins like this:

I have had not so good of a week.

Well, Monday was a pretty good day, if you don’t count Hamburger Surprise at lunch and Margaret’s mother coming to get her. Or the stuff that happened in the principal’s office when I got sent there to explain that Margaret’s hair was not my fault and besides she looks okay without it, but I couldn’t because Principal Rice was gone, trying to calm down Margaret’s mother.

Someone should tell you not to answer the phone in the principal’s office, if that’s a rule.

Immediately, we get a strong sense of character; Clementine is the sort of girl who gets in trouble and doesn’t always understand why she is in trouble. The setting is minimal, but clear: we are in a school setting, specifically, in the principal’s office. That’s enough. The setting is conveyed with humor, when Clementine answers the phone in the principal’s office.

Telling details include these: Hamburger Surprise, Margaret’s mother (we know the other main character right away), Principal Rice (a recurring character), and of course, the phone.

Put characters into motion within the setting.It’s not enough just to tell us where we are when the story opens. Stories move along better when you put the character into motion within the setting.

Economy of words. Pennypacker uses an economy of words, not taking the time to describe the school cafeteria or the principal’s office. She lets them stand as generic settings, except for the Hamburger Surprise and the phone. For this story, it’s enough.

Focus on moving the story forward. Instead of droning on with a long description of the principal’s office, the focus is on moving the story ahead. For this story, that means strong characterization because it is more of a character story than anything else.

For your story, decide what is the most important details in the opening setting, then move quickly into the action of the story. Try to use those Telling Details within the context of character movement or characterization.

The main goal? Don’t let the reader get lost. Give enough information to orient the reader to your story, but do it with an economy of words that gets the reader turning the pages. You need just enough information–and no more.

Thank you for the post! You’ve given me some food for thought in my current WIP, which is a little long-winded in the beginning. Basically, it’s all about voice. Great advice!