The process of revising your novel or story is a series of decisions and understanding the decision process can strengthen your revision process.

Avoid Narrow Framing of the Story

You get a letter from an editor that says something like this: “When Michelle is shot with an arrow, I wonder if she really needs to die. What if she avoids the arrow entirely?”

This frames the revision in terms of whether or not Michelle will be shot with an arrow and then die. That’s too narrow a context for a revision decision, and leaves out many alternate options. What if, she is shot in the leg and can’t walk; or, she is shot in the eye and can’t see; or, she is shot and runs a fever and recovers; or, she avoids the arrow, but Jillian is shot instead; or, (fill in the blank)__________.

Or, you may get a revision note that says the final chapter/climax scene doesn’t have enough excitement and needs more action. Maybe. But what if you revise it, concentrating on the mood the scene evokes, working to make it tense and emotion-filled? Maybe the problem is Mood, not amount of Action present.

When you are presented with only two options, don’t accept that narrow framing of the revision question. You don’t have to answer a “whether or not” question. Work to find other alternates. Editors don’t care HOW you make the story work, only that you do something that works.

You wonder whether or not your character should be red-headed. Narrowly framed questions like this look at the revision in isolated chunks and that’s not helpful. Instead, ask, “How will the character’s hair color influence the story? What if she were blond? Brunette? Red? Black? White?” You don’t just want to know the effect in a small section of the story, but across the whole novel. That’s giving yourself some real options that can lead to decisions that create a stronger revision.

Remove the current option. One trick to make sure you are asking more open-ended questions is to remove the current option; that forces you to take a wider look at your story and its context.

Ask: What if there was no archer, no arrow? What if Michelle never walked into that dark woods where the archer was hiding? What scene could replace this one?

Recognize: The final chapter/scene isn’t working–yet.

Ask: What options do I have to improve the storytelling here?

Multiple answers: Add action, revise for mood, create a totally new scene, keep the action the same but change the setting, keep the setting but change the action, create a different emotional context, and so on.

Multi-track to Give Yourself Options

You’ve heard it suggested before: write ten openings to your story. Why do psychologists who study decision-making agree that this is good advice? Because multiple options create a real choice. (I am not talking about multi-tasking here, where you try to do 10 things at the same time; rather, you have multiple tracks ongoing, which gives you choices.)

For example, if you want to buy a house, you don’t just look at one house and make an offer. You would look at many houses, over an extended period of time. Or, to bring it back to publishing, when a book designer presents possible book covers, they don’t just do one cover with minor variations (do you want red or black type; should the typeface be 12pt or 16pt). Instead, they work to bring several totally different concepts to the table.

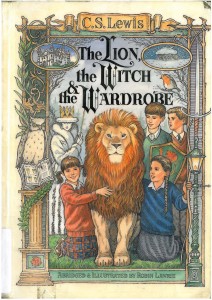

What do you think of this cover for The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe?

How does it compare to the other previous covers? Each has a distinct visual style. You want the same range of options when you revise.

Researchers say it is much better to work simultaneously on several options, rather than to do them in sequence. In other words, write ten opening sentences and then choose where to go next. This is a stronger way of working than to write an opening sentence and follow it with an opening scene; then write a second opening sentence and alternate opening scene; repeat with a third. Working simultaneously on several options yields more creativity and does it faster.

When you create these options for yourself, beware of sham options, or of writing options that obviously will not work. Options that are too bold, the wrong tone, too clichéd, or otherwise obviously off the mark for this novel—these are not real options.

Which of these five would you say are sham options for an opening sentence for a Cinderella story? Which are real options?

- Once, long ago and far away, in a forgotten land, in a forlorn castle, there lived a girl whose mother had died.

- This is the story of Cinderella.

- The kitchen maid sank onto a small stool beside the fire and thrust her feet and hands toward the meager flame, ignoring the cinders that smeared the sole of her boots, permeated the thin fabric of her skirt. She was cold. Bone-cold and weary.

- Cinderella, dressed in yellow, went upstairs to kiss a fellow.

- The new step-mother arrived on a blustery winter day, bringing color and hope to the grieving castle.

When you are stuck on a revision decision, work to give yourself multiple real options. Don’t get stuck asking, should whether or not Michelle will get shot and die or not? Widen the context and find other options.

Overcoming Writer’s Block

What if you really are stumped and the dreaded Writer’s Block is looming on the horizon?

First, look at your manuscript for Bright Spots. I know—in our zeal to revise and improve our mss, we focus so much on places where things are going wrong, that we forget to acknowledge the places where things are going right. This revision strategy asks you to look for Bright Spots, Golden Words (highlight these with yellow marker), Emotional Scenes that make the reader laugh or weep, Exciting Action, or any other place where the writing worked. Try to determine, what made it work?

What did you do well? Can you clone that success?

Approach a scene in the same way as before. What was your process for writing that scene? Repeat it for the scene where you are stuck. How did you create those emotions? Did you concentrate on reliving an emotional episode from your life? Did you mechanically go through and question every verb?

Look at your process, your inspiration, your word choices, the rhythm of the sentences—anything that worked before—and clone it.

If your own Bright Spots don’t help enough, then look for a Mentor Text, someone else’s writing that does what you want to do and try to clone that Bright Spot. Don’t worry about wholesale copying from someone else; you will add your own spin to it. You’re only looking to borrow a storytelling strategy.

Look first at stories similar to yours: if you write YA mystery, look to other YA mysteries. If you can’t find a Mentor Text there, though, don’t hesitate to look farther afield. Maybe a historical non-fiction uses some diary entries to create a sense of historical validity. Could you use fictional diary entries to do the same thing in your story?

Fill in this:

This revision problem is similar to ____________(title of mentor text). This book, solved a storytelling problem similar to mine by________________________.

In other word, you just used an analogy, comparing your storytelling problem to another book/story. If the Mentor Text used a first-person point-of-view, maybe that will work for your story, too. If the Mentor Text used a particularly effective description of the setting—even if the settings are vastly different—maybe that strategy will work in your story.

A variation of this would be to look at Best Practices of writing a novel. For example, Best Practices says that you should never add a flashback to the opening chapter. Oops! You did that. We read many books on how to write a novel, looking for these “best practices,” advice on how to write and revise better. And you would be foolish to ignore creative writing Best Practices. These are a sort of Playlist of Bright Spots.

However, you may also want to try doing the exact opposite of Best Practices. Nothing says it can’t work, it will just take more creativity to make it work.

When you revise a novel or story, you are making a series of decisions, important ones. Look at your decision-making processes to see if you can make smarter decisions and make them faster.

Darcy,

I just want to say thank you for your wonderful column. I only subscribe to a few writer’s blogs and I have found yours to be very helpful. I happen to be in revision right now so today’s advice was particularly helpful! I feel like I have a writing friend in you. I’ll let you know when my book gets published! I am such an optimist!

Cerissa: It makes me happy that you consider me a friend!

And yes, I always love to hear good news!

Darcy

Thanks for this, Darcy. I am nowhere near approaching an editor – I’m just learning, but I have experienced this kind of dilemma already on my own… asking myself, what if this or that detail is different. And those questions always overwhelm me. Because there are infinite choices for every detail!

This just makes so much sense, and I appreciate you clarifying it so well. Thanks.

Darcy, this post is knee-deep in great stuff. Thanks for all your helpful ideas!

Fantastic post, Darcy. Such great ideas and advice here.